Youtube video: https://youtu.be/f_oNDGQYqnc

Introduction

Pointers are a frequently confusing topic for intermediate computer science students. A misunderstanding about the arithmetic surrounding pointers or even the very nature of what a pointer is, is a significant barrier to students that need to code in C or C++, or do tasks with large data that needs to be efficient. By the end, you’ll have a working understanding of pointers and how to modify them with math.

What are Pointers

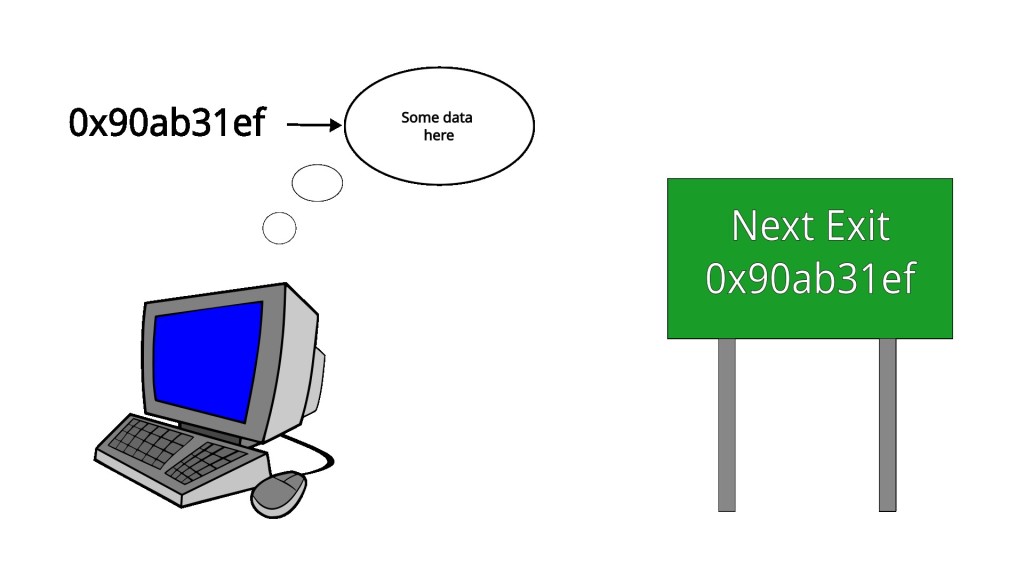

Simply put, a pointer is a location in memory. Sure, when you print a pointer out, it is a hexidecimal number that looks like this 0x90ab31ef, but you can think of it as a big arrow or highway sign telling you, go here to find something.

In code, pointers are often declared like this:

int *some_variable

char *another_variableThe important thing to pay attention to is the inclusion of the *.

Next, call the malloc function to ask the computer to give you a location in memory of a certain size in bytes. But, be careful, different types can be different sizes in bytes, so malloc calls are often done like so:

int *some_variable = malloc(2 * sizeof(int));

char *another_variable = malloc(3 * sizeof(char));Since the function sizeof returns the number of bytes in a given type, multiplying like this is the equivalent of asking for a pointer to a chunk of memory large enough to fit n of a given type. In the code example, some_variable is now a pointer to a chunk of memory that can store two integers, and another_variable is a pointer to a chunk of memory that can store three characters.

Now if you try printing out the variables the output will look like this

int *some_variable = malloc(2 * sizeof(int));

char *another_variable = malloc(3 * sizeof(char));

print(some_variable) -> 0x8103813f

print(another_variable) -> 0xbba820adwhich can be confusing because the two pointers look exactly the same. And, to make it momentarily even more confusing, they look the same because they are the same. Pointers, no matter what, are just locations in memory. The differing types like int and char are there to inform the programmer what is present at the location in memory being pointed at. No matter the other associated types, a pointer will always indicate a point in memory where you can go to and find something.

To explain this further, we’re going to talk about street addresses.

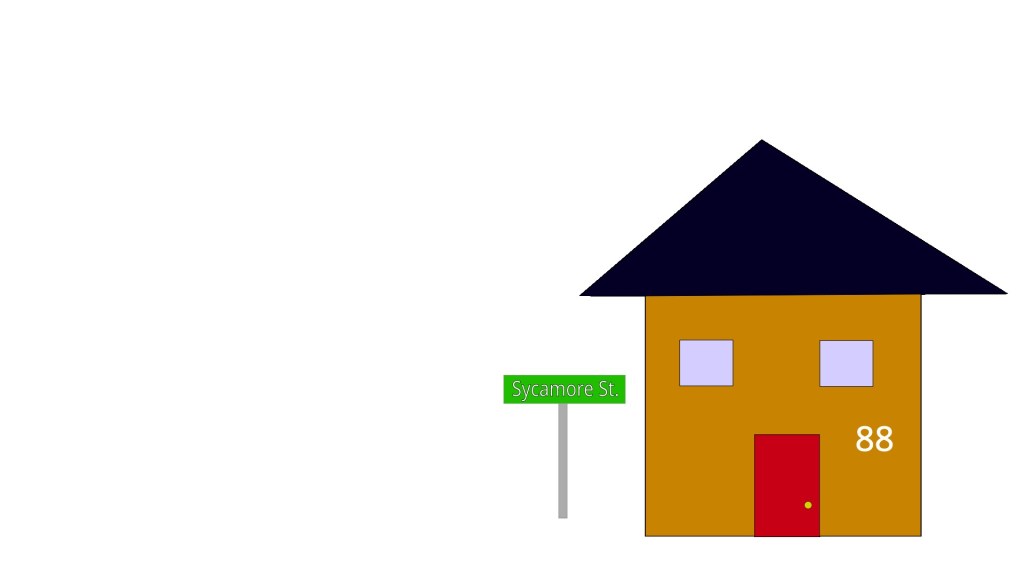

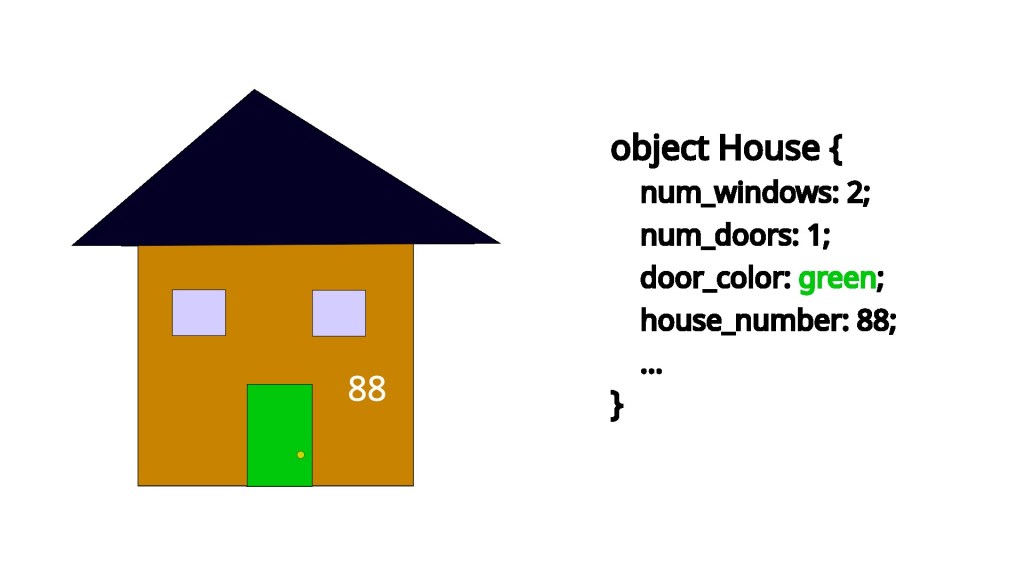

Analogy about house addresses

For this example, the house we’re going to look is on Sycamore Street with the house number of 88. So, the street address for the house can be written as 88 Sycamore Street. To lean on pseudocode a bit, what we’ve just done here would look like this in code

house *house_ptr;

print(house_ptr);// 88 Sycamore StreetNotice how printing the house pointer prints out the street address, similarly to how earlier printing out the code pointer printed out a memory address. Also, similar to how you can share the house address around and always be sure that it refers to the same location, the same is true for pointers in computer code. 88 Sycamore should always refer to that location, a memory pointer is the same.

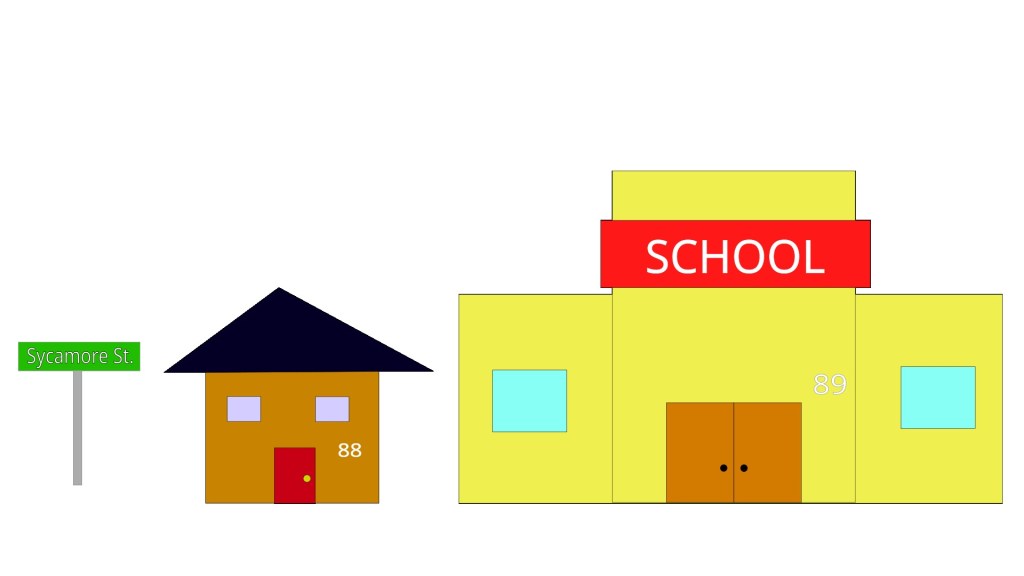

Now for the concept of different types. Street addresses aren’t used to exclusively refer to houses. For example, let 89 Sycamore Street refer to a school.

school *school_ptr;

print(school_ptr); // 89 Sycamore StreetAgain, similar to pointers, notice that printing the street addresses for the school looks exactly the same. It doesn’t matter that the street address is referring to something different. You would only know the difference by the type annotation or actually going to the destination.

int * -> Go here to find an `int`

char * -> Go here to find a `char`

house * -> Go here to find a `house`

school * -> Go here to find a `school` Why use pointers and how you’re using pointers already without even knowing it

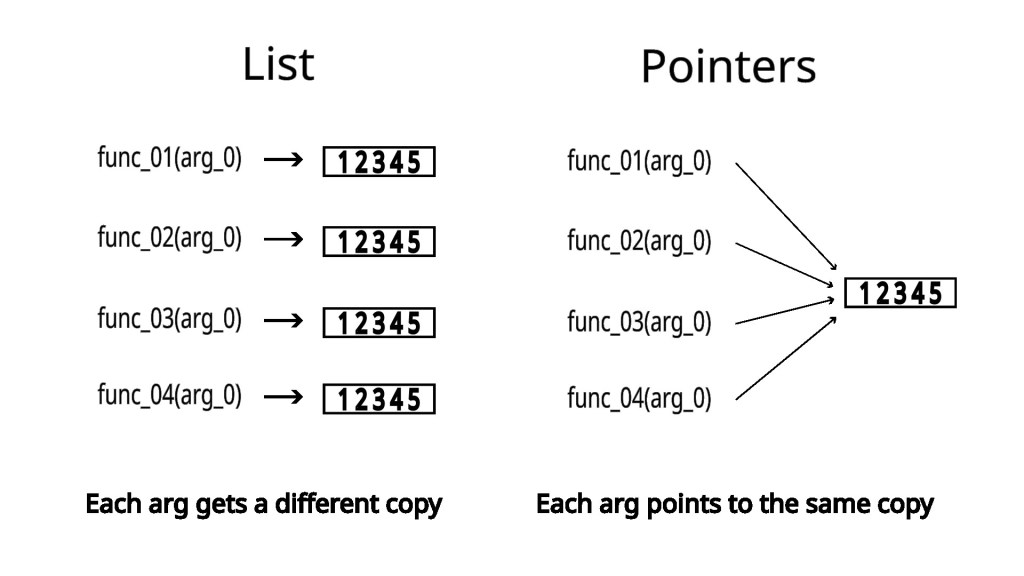

The question remains, why use pointers in the first place? The examples so far haven’t been convincing. Rather than have a pointer to an int, why not just have an int variable. The reason why this doesn’t make sense is because pointers often refer to a sequence of a given type rather than just one instance. In this code, we allocate a space that can hold ten ints.

int *some_variable = malloc(10 * sizeof(int));You might be wondering, how is this different from a list. The big difference is in how lists and pointers get passed around in functions. Depending on the language implementation, lists can get duplicated and copied as they get passed in as different arguments to functions. Pointers will always have that memory address just passed around.

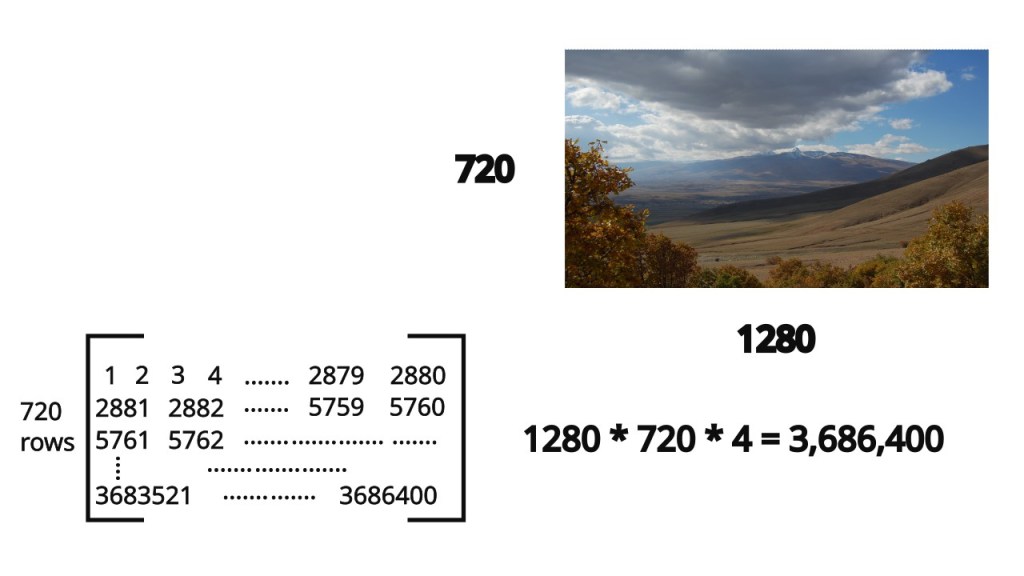

This becomes really important when you’re dealing with code that needs to be fast. A good example are video game rendering engines or anything that deals with images. A 1280×720 video frame with RGBA encoding can be represented as a sequence of 3,686,400 numbers. I have another article on how this is possible here.

In fact, you’re probably using pointers in your code already without even knowing. If you pass in an object to a function and then change a value on that object, have you noticed that when you go back to the original, calling function that the value remains changed? That because the language you’re using passed the object around as a pointer to save what could be a potentially expensive operation of allocating and copying to get a new object.

This is all well and good in the abstract, so let’s quickly take a look at video games for a practical example. First, starting a game and loading take so long because that’s when the expensive memory allocation and copying steps take place. As you load from one level in a game to another, all the assets for that next level get loaded from the disk into memory. This allows the assets to have a pointer assigned to them that can be used later (this looks like the malloc call from earlier, but much larger). This is why modern games use so much RAM; they need to load their large assets into memory for later use.

Having the data in memory and those pointers are how frames can be generated so quickly. Instead of having to do the slow, expensive operation of allocating memory and copying the asset from disk, the game can instead quickly use the pointer to access the asset where it is already loaded into memory to render the frame.

How does pointer math work

The initial pointer only points to the beginning of the allocated space. So, with

int *var = malloc(10 * sizeof(int));var is only pointing at the the beginning of the allocated section. Pointer math is how you access the remaining nine locations.

Since the memory allocated is sequential, we can access the next block of memory by adding to the pointer.

Pointer math functions on bytes, so adding the number of bytes an integer takes up to the pointer, advances the pointer enough in memory to point to the next available spot for an integer. This is what it looks like in actual numbers

assume sizeof(int) == 4

assume var == 0x2aadb39f

0x2aadb39f + 4 -> 0x2aadb3a3 In this code, 0x2aadb39f is the location of the first int and 0x2aadb3a3 is the location of the second int. And, you can keep incrementing the pointer to access the next slots.

When incrementing pointers, it’s important to keep track of the size of the data you’re working with. In the example, the sizeof(int) was 4. However, incrementing a pointer isn’t as simple as adding 4 every time. Different computers have different sizes for int, so it will always be more accurate to have the code read var + sizeof(int). This way all kinds of computers are accounted for.

EDIT NOTE: To be clear, most computers handle this sort of incrementing for you, and size is accounted for . This example is only meant to make you more familiar with the internals of what is happening when adding to a pointer. var + 1 will, in practice, move the pointer forward by 1 unit of the size associated with the type. The code in this section is pseudocode.

Additionally, different data have different sizes, so it’s critical to increment by the appropriate amount. Let’s look at the following code for why.

assume sizeof(int) == 4

assume sizeof(double) == 8

int *var = malloc(10 * sizeof(int));

var = var + sizeof(double);If we aren’t careful, we can increment the int pointer by too much and skip some of the data. Alternatively, if the roles were reversed,

double *var = malloc(5 * sizeof(double));

var = var + sizeof(int);incrementing by an inappropriate amount would place you in the middle of a double which would make the information your program is parsing nonsense.

Now, there is some hope for this complicated mess. Some programming languages provide niceties that allow you to access elements in a pointer using list-like syntax and increment using ++. So, you could access the second location with var[1] instead of having to manually increment the pointer. Similarly, if you wanted to permanently update the pointer, you could use ++ instead of var = var + sizeof(int).

When you’re using pointers, even if you’re diligent about sizes, you still have to be careful how much you increment. Even though, we only allocated for ten ints we can keep adding to the pointer and start to access sections of memory outside of the allocated location. This will cause the program to do unexpected things and can be a security vulnerability.

The crazy things possible when pointer math is wrong

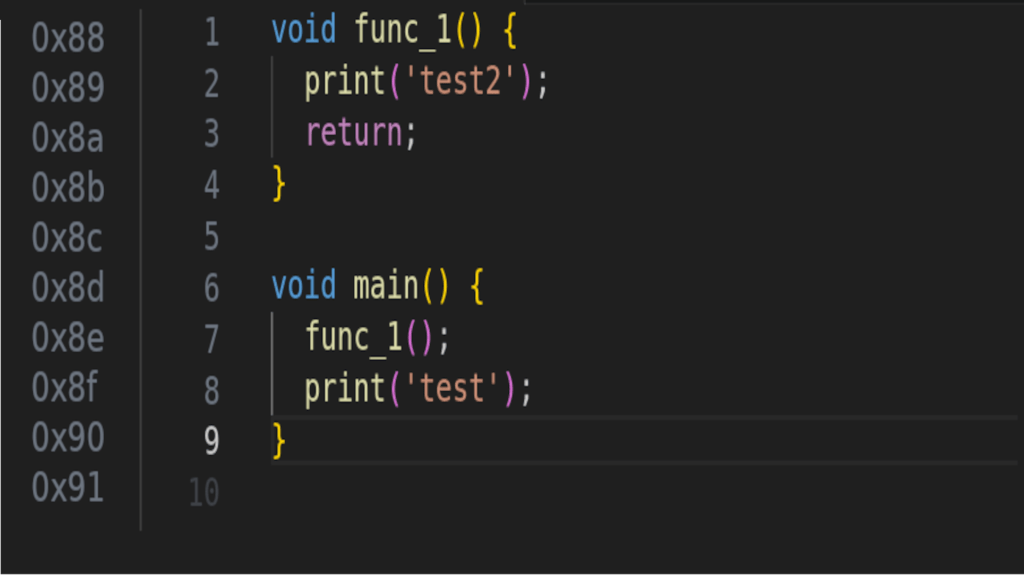

Pointers aren’t restricted to pointing at int and objects. Pointers are just memory addresses, and so they can point to functions and even specific lines of code. When a computer program is loaded into memory, each command is given a memory address. This address is then used to facilitate operations like calling a function or return.

For example, when func_1() is called, the program jumps to the hex-address for the first line in func_1() and starts executing. Then when func_1() returns the program jumps back to the hex-address for print(‘test’) and continues executing the program.

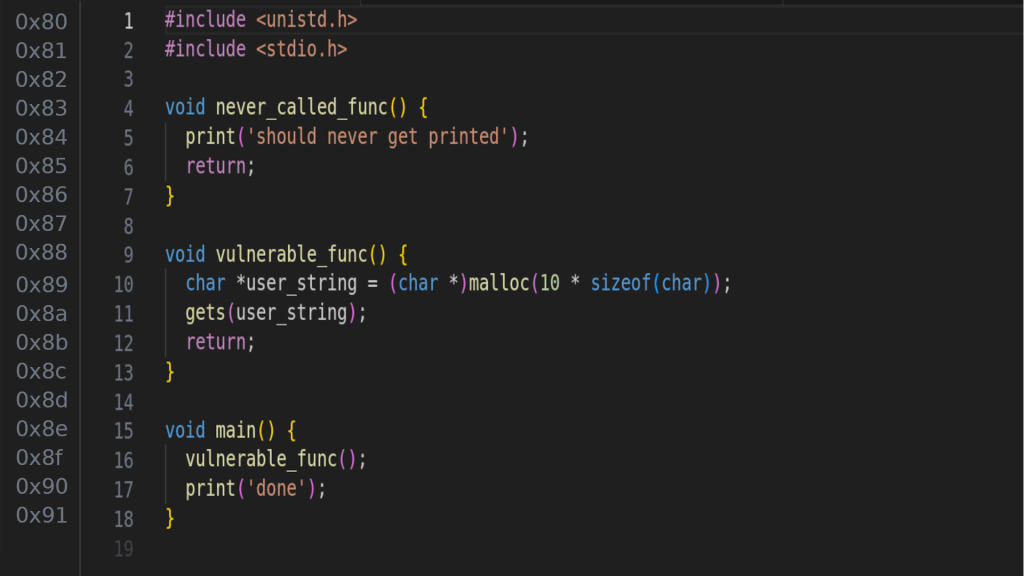

Now, let’s look at a program with a vulnerability.

Specifically, the vulnerability is on line 10 when gets(user_string) is called. gets() is a method that takes user input from stdin and puts it in the given argument. However, it doesn’t restrict the size of the input, so even though user_string can only store 10 chars there’s nothing stopping a user from inputting 20 or even 1000. This allows a malicious user to start overwriting locations in memory after the area allocated for user_string.

Since the call to malloc only requested 10 chars all a malicious user would have to do is provide eleven characters to the program to start modifying locations in memory they shouldn’t have access to.

With some careful tweaking of the input by the malicious user, this can be used to overwrite the memory address that the call to return is going to use on line 11. That memory address could be modified to point at never_called_func() at 0x83, and therefore calling it with no other lines of code referencing it.

In fact, notice the top line of the program #include <unistd.h>. This is a standard C library that contains such functions as exec(). At this point, being able to call never_called_func() is an irrelevant point because you can modify the memory address used by return to point to exec() and just execute any program on the computer system.

This vulnerability is called a stack overflow and was one of the top ten vulnerabilities covered by OWASP.

With all the doom and gloom out of the way, let’s look at some fun, real life examples of stack overflows.

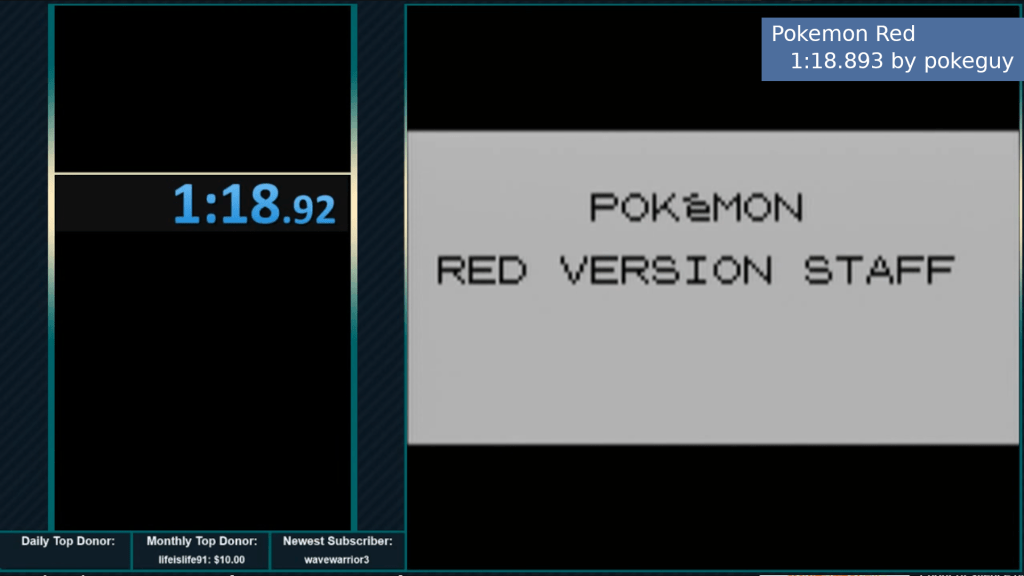

The Pokemon Blue Any % speed-run uses a stack overflow (technically underflow) to complete the game in 1m 18s 893ms.

The first thing the speed-runner, pokeguy, does is corrupt his save. This then allows him to execute the overflow. In moving items and Pokemon around in his bag, pokeguy is using the internal values of those items to write in memory. Compared to the earlier example, this is the user exploiting gets(). By the end, he’s switched the what should happen when he exits the menu with the code that warps him to the Hall of Fame. A guide on how to do this can be found here.

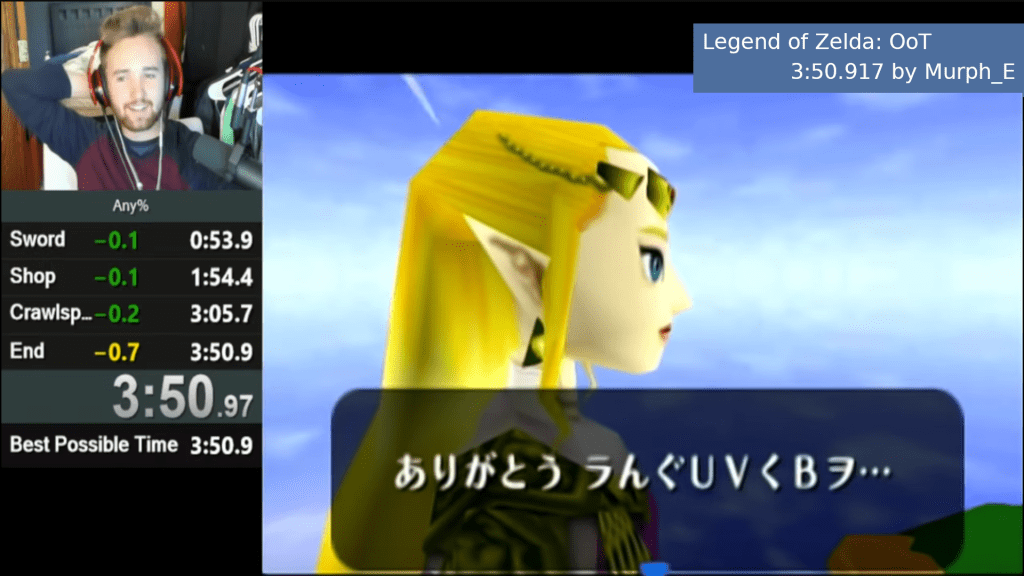

Another famous speed-run that uses this sort of computer exploit is Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time Any% run that finishes in 3m 50s 950ms.

When the speed-runner, Murph_E, is doing all sorts of flips in specific locations while picking up and dropping certain items while holding the bomb and facing certain directions while going through Kokiri Forest, they are performing a stack overflow exploit to modify the memory so that the when the final dodge roll occurs, it sends him to the end of the game.

The fun thing about these kinds of exploits is that if the user has the right items, they can go anywhere in the game or modify anything in memory. Using these same sorts of exploits to modify pointers it’s possible to give yourself all the badges, infinite rare candies, infinite faeries, or even just teleport you wherever. Speed-runs just have a specific goal in mind, which makes those cases not useful.

All that is to say that this is all possible by manipulating pointers and using them to modify the data they are pointing to.

Conclusion

Pointers are references to specific chunks of memory that data can be found at. This functions in the same way that street addresses do for houses.

If you add 1 to a pointer, you move forward one byte. However, many primitives and objects are larger than one byte in size, so you need to be careful to increment your pointers by sizeof(TYPE) * NUM_OF_SPACES_FORWARD. The same applies if you’re going backwards with subtraction.

By changing data at the other end of a pointer, all subsequent use of that pointer will be to the modified data. This is a powerful tool for program efficiency, but is also the source of security vulnerabilities. So, it’s important that pointers are used with proper care and proper testing.

For more information about stack overflows and how to prevent them, visit the OWASP page. They refer to the bug by the name of buffer overflow.

I hope that though this article was able to clarify the often confusing topic of pointers. If you have any questions, please comment below, and I’ll do my best to answer them. Thank you and have a wonderful day.

Citations

- Pokemon Any% Speedrun Youtube video

- Pokemon Any% Speedrun Guide

- Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time Any% Speedrun Youtube video

- OWASP Stack Overflow Explanation

- By Felix Khachatrian – https://www.flickr.com/photos/felix-khachatrian/3101218088/in/set-72157611056749981/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5558781

Licenses

Notes

- Since the creation of this post, the Pokemon Blue Any% WR has been improved by Grogir with the time of 1m 18s 793ms.

Leave a comment