Youtube Video Link

Introduction

Often, when media shows a machine learning technique being applied to an image, there’s a diagram that shows an image being sent into some kind of neural network.

In those articles, an image like this might give the reader something nice to look at or explain some parts of the neural network the article is focusing on. However, for readers that aren’t familiar with how images are transformed for machine learning, these kinds of images can often lead to confusion. Even many courses aren’t clear on the processing that needs to occur so that images can be used to a train neural network.

!["Side by side scenic view and bits [2]"](https://numbersallthewaydown.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/split_scenic_and_1s_0s.png?w=1024)

Computers don’t perceive the world in the same way we do. So, a common point of confusion for students just starting out with machine learning is how to bridge the gap between fully colored images and the sequence of numbers that a computer uses. We will focus on explaining this gap in the following sections.

Prerequisites for understanding

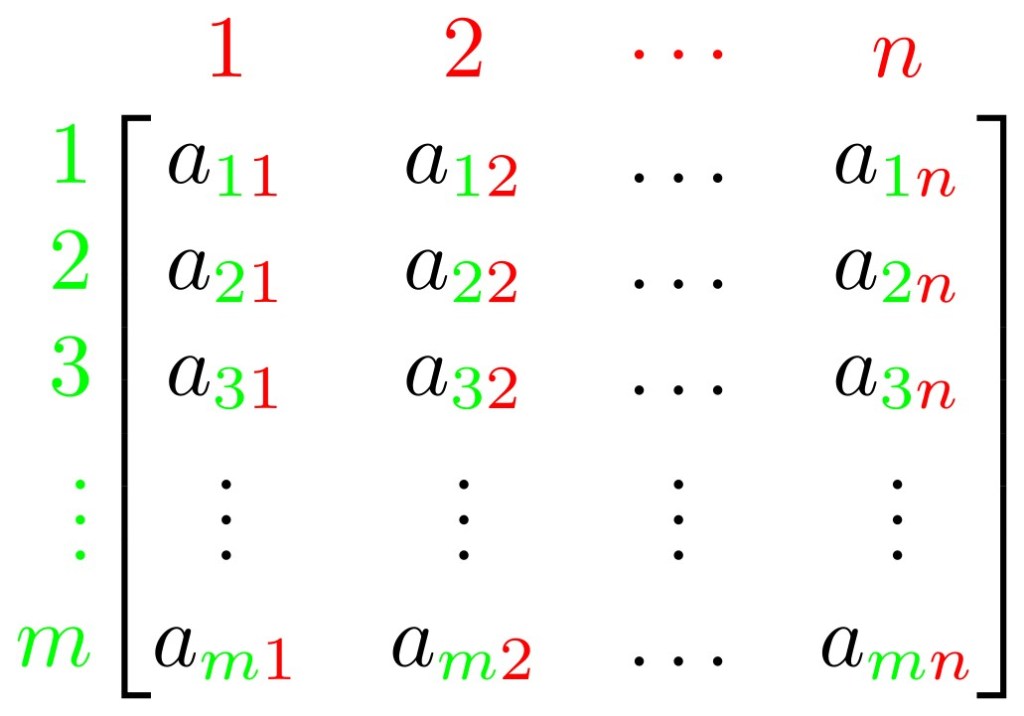

To get the most out of this explanation, it’s helpful to have a basic understanding of linear algebra (specifically the terminology surrounding vectors and matrices) and how RGBA encoding works for images. However, prior knowledge is not strictly necessary as I will be explaining the basics of both topics as they relate to this article.

A lot of the vocabulary of linear algebra is used in machine learning due to the considerable overlap in the fields, and this article will continue to do the same. This vocabulary will be especially important as we will be discussing how to represent an image as a vector of numbers.

As for encoding, the more you know about how an image can be represented using RGBA, the easier it’s going to be to understand this article. I will still explain the basics necessary for processing an image, it just might take some more time for the {viewer/reader} to develop a proper understanding of the process.

Why convert an image into numbers

Images need to be serialized in some way to be stored on computers. Serialization is the process by which the information about how things should look in the picture, like the colors and the location of those colors, get encoded for the computer to store on a hard drive and then eventually retrieve at some point down the line. If you’re viewing a picture on an electronic screen, that image is already encoded in some way. Different file formats (such as pngs, jpegs, and more) encode images in different ways.

The images in their base file encoding often aren’t the easiest to work with for the purposes of machine learning. File formats encodings often have extra, meta information in them to aid in their proper rendering by the programs that are going to display them (think Paint, Photoshop, or Gimp). This metadata often includes: the type of image, the image’s dimensions, the specific color encoding used in the image, and more. As a result, the images we start out with need to be altered and standardized to make them easier to work with. Different formats require different kinds of processing, and sometimes different machine learning problems require specific parts of the metadata. However, no matter the case some form of standardization is going to be necessary before an image is ready for use in the training of a neural network.

This standardization process, also known as preprocessing, is critical because it forces the images into a shared format and removes any extra information that can mess up your future machine learning results. A common beginning step of preprocessing is to convert the images into an RGBA vector.

“Image of pretty scenic image with a specific part pointed out to show RGB pixels”

For the unfamiliar, RGBA is a way that computers store color information. R stands for the color red, G stands for the color green, B stands for the color blue, and *A* stands for the concept of alpha, which refers to how see-through or opaque the combination of RGB colors should be. Alpha allows you to stack multiple RGB colors on top of each other and show them in some combination if one or the other is see-through. A good example of this is layering an image on top of text in a document. If the image is see-through then you can still see the text underneath. This is what alpha controls.

Each value in an RGBA code can be assigned a number that describes what the color should be. The most common standard is for the RGB values to be represented by numbers comprised of 8 bits, meaning that they can range in value from 0 to 255. The higher the number, the more of that color you have in the end product. So, if the RGB component of a color is 255, 0, 0 the resulting color would be completely red. Similarly, if the RGB value was 255, 0, 255 that would mean the color is meant to be a combination of pure red and pure blue, which would result in the color purple. Since each color value is composed of 8 bits each RGB value can be represented as a number between 0 and 16,777,215 aka 224 on account of needing to include the 8+8+8=24 bits needed for each of the color values. To reference an earlier example, the color purple would be 255, 0, 255 which, in bit form would be 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1. This could then be converted into a number in base 10 16,711,935. In this way, each color in an image can be represented as a single number.

Alpha is a number between 0 and 1 and is often discarded in these sorts of analyses since it is a floating point number.

Images are shown in two dimensions (width by height), so it is not immediately obvious how a two-dimensional image gets converted into a one-dimensional vector of RGB numbers. An easy visual reminder for this two to one dimension process is to imagine unraveling the image like a sweater unravels in a cartoon when you pull on a loose thread.

In the gif, the sweater exists in multiple dimensions, but, by pulling on the string and unraveling it, the sweater is transformed into a one-dimensional object. If we consider an image as a series of RGBA pixel information in multiple dimensions, we can accomplish the same unraveling using the following process. For this example, the image is 1280×720. This is a common image resolution where the image has a width of 1280 pixels and a height of 720 pixels. In other words, each row in the image has 1280 pixels and there are 720 rows of 1280 pixels. Since we’ve already determined that an RGBA pixel can be represented by an integer, that means that each row of pixels in this image can be represented by 1280 integers. It then follows that each row can be represented by a vector consisting of 1280 integers.

Now, with all this in mind, I pose the following question, where do you expect the 1281st pixel to be? How about the 2561st (1280 + 1280 + 1) pixel? If you responded with the beginning of the 2nd and 3rd rows respectively, you would be correct. When feeding an image into a neural network, the exact width and height position need not matter from the perspective of the neural network. Since the coordinate position need not matter, there is no reason why we can’t consider the first pixel on the second row as the same as the 1281st pixel in a one dimensional vector.

Then this vector of numbers can be fed into a neural network that has a first layer of 921,600 (1280*720) nodes. From there, it’s just a matter of doing this to all images in the dataset and training the neural network to generate the final model.

This is a basic process for how to take an image on disk and feed it into the first layer of your neural network. Hopefully this explanation was able to help you bridge that often confusing gap for students just starting out in the field of machine learning. Now, to delve a bit more into the practical side of machine learning, it’s important to note that this is likely only one of many potential preprocessing steps that need to be done to an image prior to being used to train a neural network. Other preprocessing steps to remove excess information and standardize the images are often done for the sake of efficiency and consistency in results when training a machine learning model.

Further preprocessing on an RGBA vector string

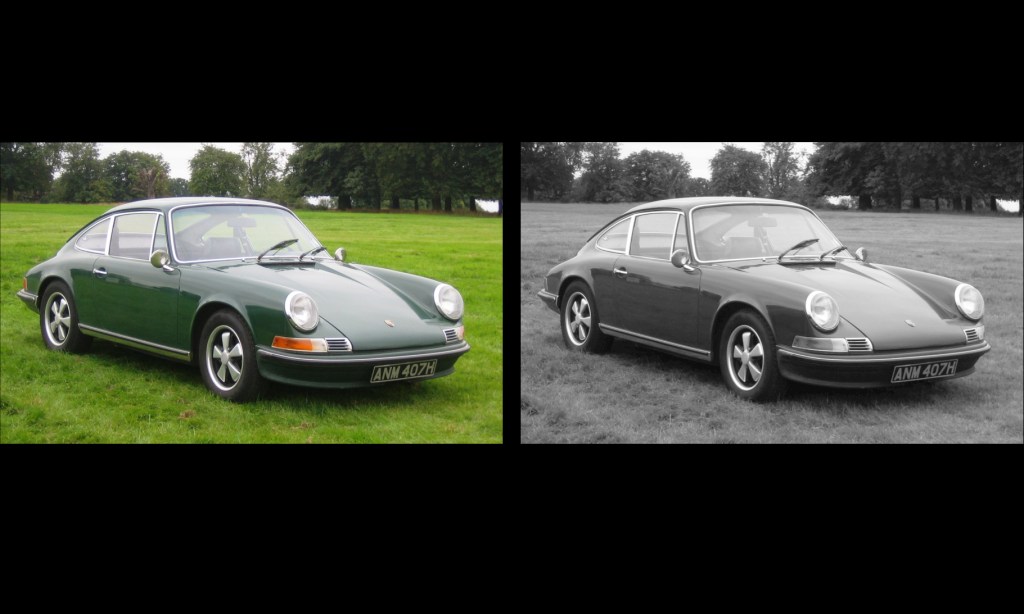

In practice, it’s unlikely that you’ll use an RGBA vector to represent your images. One of the first pieces of extra information, to be removed from images is color. So, the RGBA information gets further preprocessed into grayscale. Each pixel in grayscale is commonly represented using only 8 bits (aka a number between 0 and 255). Compare this to the 24 bits that are commonly used to represent an RGB color, and you can see why removing color is so effective at reducing the amount of information that needs to be included. If your machine learning task can be accomplished in grayscale, you’ve decreased the amount of potential color values you have to consider by a factor of 65,536 (224 / 28). The more values that you have to account for (aka the noisier your data) the harder it’s going to be to train a model to pick out the relevant features.

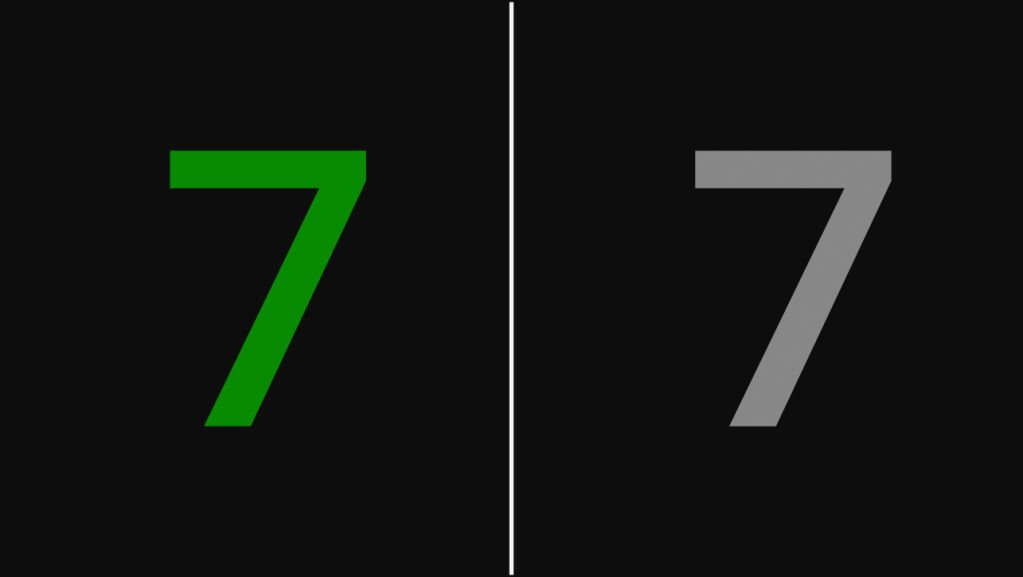

Machine learning tasks like object detection or object recognition often don’t require color. For example, if you want to make a model that can recognize the number 7, it doesn’t matter if it is a colored 7 or a grayscale 7.

Similarly, with object detection, you don’t need color to know if an object is somewhere. The car is either in the image, or it isn’t.

You can even further reduce the information being passed in by using techniques similar to run-length encodings to get rid of irrelevant in-between data in your images. However, these will not be covered here as this is meant to serve only as an introduction.

Unless you have the resources to train large models with large amounts of data (think GPT 4 or Stable Diffusion), a good rule of thumb to follow is that you want to use as little information as possible while still keeping the input data representative of the task that you’re trying to train for. The more data you include, the higher the potential for noise in that data to derail your training by either taking too long for your training terminate or reaching a local minima that isn’t representative of the population. In the case of taking too long, you are limited by the time and money that you have access too, and the longer it takes to train a model, the more time and money you have to spend.

In the earlier example about recognizing the number 7, removing the color kept the training data representative of what can be expected to be found in the real world, as we can modify all incoming data from the population to be in grayscale, with no downside in terms of recognition. If we decided to keep the color information, it the becomes more likely for the model to reach a local minima based on some characteristic that isn’t relevant to the task.

Notably, if we don’t filter out color, we can reach a local minima where the color of the incoming number influences whether or not a 7 is recognized. Hypothetically, if a large number of our training data had 7s that, by chance, happened to be blue or yellow, then, because of that small coincidence, it’s possible that the model will learn to associate yellow and blue with 7s rather than focusing in on the desired shape of the number. The model is now stuck at an undesired local minima which will likely result in a model that falsely recognizes non-7 numbers that are blue or yellow as 7s and 7s that aren’t blue or yellow as being non-7. For this reason, you are better off and are likely to get more consistent results if you remove the unnecessary information, like color, from your images prior to training your model.

Conclusion

In order for images to be used in machine learning, they need to be converted from their base file format into a vector of numbers. This sequence of numbers is how the neural network will perceive the image, in contrast to the two-dimensional fully colored images that we are used to seeing on a computer monitor. Preprocessing the image into a sequence of numbers often involves multiple steps that strip out extra information found in the image to save both time and money and results in a more consistent outcome when training the model.

Citations

Assets

- [1] By Aphex34 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45679374

- [2] By Felix Khachatrian – https://www.flickr.com/photos/felix-khachatrian/3101218088/in/set-72157611056749981/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5558781

- [3] By Mavaddat – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=126575964

- [4] By Charles01 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4630784

- [5] Shawn the Sheep cartoon

Leave a reply to How Pointers Work and the Weird Math Behind Them – Numbers All The Way Down Cancel reply